Learning the Use of Symbolic Means: Dalits, Ambedkar Statues and the State in Uttar Pradesh

by Nicolas Jaoul

by Nicolas Jaoul

(This article has been republished with the author’s permission.)

The Ambedkar statue stands as a major feature of the Dalit movement. In the media, the Dalit emphasis on symbolic politics has been dismissed as mere tokenism, and the Ambedkar icon has been denigrated as Westernized. Despite attempts at studying Dalit politics since the BSP became one of the key players in Uttar Pradesh, there has been a lack of scholarly attention to the deeper social changes involved in the Dalits’ relationship with the state. This study of the Ambedkar statues in Uttar Pradesh tries to fill this gap by taking three dimensions into account: the iconography, the way in which the statues have spread historically, and the meanings and stakes involved for those who mobilize around them. The assumption is that the Dalits’ struggles for the imposition of their symbol in public places can contribute to an understanding of the manner in which Dalits have imagined the state and engineered strategies towards it. These statues seem to be the focal point for renewed aspirations towards democracy, while the ceremonies organized around them have provided these deprived citizens the opportunities to build some support within the state.

Acknowledgments: The title of this article is inspired by E. Zelliot’s landmark article ‘Learning the use of political means’ (1970). I would like to thank Christophe Jaffrelot, Owen Lynch and Donal Cruise O’Brien for their comments, as well as Patrick Claffey for his careful reading of a previous version. Shorter versions of the paper were presented at SOAS, London; ADRI, Patna; the G.B. Pant Institute, Allahabad; and the India International Centre, New Delhi, between May and November 2004. Last but not least, my gratitude goes to Dalit activists in UP, especially in the region of Kanpur, for generously sharing their knowledge and for their hospitality.

I. Introduction

Political symbols play a major part in the way a nation is depicted and fed into the imagination of its citizens (Anderson 1983). This symbolic work emanates generally from the official realm but, as this study will show, it may also derive from the initiatives of political parties and social organizations. Thus, different actors involved in the public sphere insist on particular symbols or ‘great men’ that express their different ideologies, different ideas of the nation and identity struggles. These political symbols appeal to people at a more private level, reflecting the internalization of a political imaginaire that contradicts the usual notion of fixed boundaries between state and society. Indeed, as this article seeks to show, it testifies to the circular influence of both in the realm of popular culture (Fuller and Harriss 2000).

The Ambedkar icon, which has become the symbol of Dalit identity, provides an interesting case study of the understanding of and strategies towards the state by the unprivileged in India. Attention to the meanings associated with symbols like the Ambedkar statues by those who mobilize around them thus assists our understanding of grassroots perceptions of Indian democracy. In the context of poverty and illiteracy where they operate, such symbolic means have profound political implications, promoting ideals of citizenship and nationhood among the politically destitute where the state has partially failed. This article seeks to emphasize the instrumental importance of the Ambedkar icon and its contribution to what Khilnani has called the ‘deep politicization’ of Indian society (Khilnani 1997).

In a recent study on the politics of a Muslim brotherhood in Senegal, Donal Cruise O’Brien goes beyond the conventional opposition between ethnicity and nationhood to consider the way ‘symbolic confrontations’ by ethnic organizations sustain participation and thus deepen the feeling of nationhood among illiterate citizens. Such increased participation implies fundamental changes in the way the disadvantaged perceive and relate to the state:

Ideas of participation include the idea that one can organize in making demands of the state, that one can bring the state to act on one’s behalf. In this deep process of social adjustment, the symbolic confrontation has a central role, promoting sectional interests, yes, but in a dialogue with the state, engaging people’s loyalties, in the long run probably strengthening the state, as an institution with its place in the citizens’ imagination (O’Brien 2003: 29).

The author emphasizes the pedagogic dimension of the symbol, which ‘is part of the emergence of a political language, enabling larger numbers of people to define themselves in relation to the state, if you will to make sense of the state’ (O’Brien 2003: 26). O’Brien’s argument can be extended to other post-colonial contexts, where the politicization of the lower orders and the use of religious symbols often go hand in hand. O’Brien takes the example of the Indian struggle for freedom, in which Gandhi used Hindu symbols to appeal to the rural masses and bring them together with the Congress against the colonial state. He also notes how this political pedagogy alienated Indian Muslims who were unable to find themselves reflected in a nation defined by Hindu symbols, thus contributing to the communalization process that led to Partition. This argument can also be applied to the case of radical ‘Untouchables’/Scheduled Castes[1], led by B.R. Ambedkar (1891–1956), who distrusted Gandhi’s charitable attitude towards them. The latter’s reformed Hinduism was still too close to caste hierarchy to be acceptable to those who suffered from untouchability, and whose leaders feared for their future in an upper-caste-dominated independent India (Ambedkar 1945).

Different terms are used to refer to those segments of the population treated as ‘Untouchables’, according to Brahminical standards, because of their ‘unclean’ occupations such as leather-work, sweeping and scavenging, weaving, cremating the dead, and so on.

The term ‘Scheduled Castes’ is an official category, framed by the colonial state in 1935 to implement special policies towards the Untouchables following the Poona Pact agreement between Gandhi and Ambedkar. The term ‘Harijan’ (‘People of God’) was invented by a Gujarati poet of the 17th century and popularised by Gandhi after 1932 in order to promote the acceptance of Untouchables by other Hindus as members of their religion. The term ‘Dalit’ (‘crushed’ or ‘oppressed’) is a less euphemistic term which has been in use since the 1910s. In fact, it was used by the Arya Samaj and later by Jagjivan Ram. (Both are considered as representing the non-radical reformist approach to Untouchability, where upper castes took the lead in promoting reform, though of course both were seen as radical compared to conservative upper-caste Hindus.) The term ‘Dalit’ became associated with radicalism when it was re-popularized in the 1970s by radical Ambedkarites such as the Dalit Panthers and later by the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). Today the use of ‘Dalit’ has become widespread in many parts of India, including UP. In this article, I use different terms, according to the historical context.

Ambedkar’s relentless and bitter struggle against Gandhi on the question of the recognition of the ‘Untouchables’ as a separate minority left its mark on their collective destiny at several levels. At the social level, the policy of positive discrimination that resulted from the compromise between the two leaders (known as the Poona Pact, 1932) encouraged education and social mobility. At the political level, Ambedkar’s nomination as the head of the Constitution Drafting Committee was a reconciliatory act by Gandhi, designed to involve the Scheduled Castes in the process of nation-building and thereby to sustain national integration (Zelliot 1988). However, despite this momentary and partial reconciliation with the Congress, Ambedkar’s struggles against Gandhi left their stigma on Dalit politics. Even though they were depicted negatively in mainstream Indian historiography, these struggles were remembered in Ambedkarite circles as a landmark episode, because of which a distinct Dalit political identity could be kept alive and nurtured after Independence.

Although Ambedkar had warned his admirers against making a cult of his personality, a move that had started in his home state of Maharashtra even before his death (Tartakov 2000), the statue, perhaps inevitably, became a tool for political mobilization after he died. The little blue statues of Ambedkar wearing a three-piece suit and holding the Indian Constitution have indeed become a common sight in contemporary slums and villages in many parts of the country.

This article narrates the history of these statues in Uttar Pradesh (UP), where the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), a political outfit led by Ambedkarite Dalits, has formed several governments since the mid-1990s. The case of Uttar Pradesh is especially interesting as far as Ambedkar statues are concerned. First, the statues have played an instrumental role in the BSP’s successful mobilizations, confirming the popular appeal of symbolic politics in a state where the Ayodhya campaign had already helped the BJP to power in the early 1990s. Second, once in power the BSP put great emphasis on the official installation of statues, which in turn motivated Dalits to install more statues in their villages. The way the state and society have emulated each other brings an interesting perspective to bear on symbolic politics and on the evolution of relations between Dalits and the state. That is, the influence of the official Ambedkar iconography on the popular statues, along with the imitation of official ceremonies in villages, reflects a process of popular learning of symbolic skills.

II. From Parliament to village: Ambedkar’s official image and its appropriation

The practice of setting up statues of political leaders on public sites was introduced into India by the British, who installed statues of soldiers and civil servants of the Raj. After Independence, the practice was continued with the installation of statues of Gandhi and regional figures of the independence movement, as well as historical figures such as Shivaji in Maharashtra. The first official statue of Ambedkar was set up in Bombay in 1962, at the Institute of Science crossing (the former Provincial Assembly) (Tartakov 2000).[2] Ambedkar was represented as an orator, dressed in a three-piece suit, his right arm and finger upraised as ‘a great man lecturing the nation’ (ibid.: 102).

According to Tartakov, the message was both to the nation — on the dangers of caste and inequality — and to his fellow Dalits, whom he urged to organize democratically to secure their rights.

In 1966, another statue made of bronze was set up in front of the National Parliament in New Delhi and unveiled by the President of India, Dr S. Radhakrishnan.[3] This national recognition of Ambedkar was a significant move, as the ‘Untouchable’ leader, despite having chaired the Constitution Committee, had been identified more or less as a traitor in the dominant political stereotype of the ruling party ever since his opposition to Gandhi at the Round Table Conference.

In the new political context of the mid-1960s, the decision to honour Ambedkar was an attempt by Indira Gandhi to woo the Ambedkarite constituency of the Republican Party of India (RPI).[4] At the Ahmedabad convention of the party in 1964, the RPI had adopted a charter of demands, focusing conspicuously (five out of ten points) on problems of poverty, minimum wage and landlessness. This emphasis on the economic demands of the landless peasants, which was designed to build an alliance of the rural poor across castes, is characteristic of the RPI’s socialistic emphasis, but the party’s first demand was for the installation of ‘a portrait of Dr Ambedkar as “Father of the Indian Constitution” in the central hall of Parliament’ (Zelliot 1970).[5] Taking up these demands, massive mobilizations took place in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Maharashtra in December 1964, when 300,000 demonstrators were arrested (Duncan 1979: 246).

According to L.R. Balley, who was the Punjab leader of the RPI at that time, Parliament officially voted to raise the statue around 1964–65, thanks to the support of the Speaker, Hukkum Singh, who had chaired Ambedkar’s welcome committee during the latter’s visit to Punjab in 1936. The Sikh politician thus wished to give Ambedkar the national recognition that he felt he deserved as one of the nation-builders.[6] Even if Ambedkar’s image did not make it to the Central Hall of Parliament, a massive bronze statue was set up outside the premises, representing him in his three-piece suit with the Constitution in one hand, the other arm pointing to the sky. The statue was made by the same official sculptor as the one in Bombay, and its main novelty was that he added the Constitution, probably to emphasize Ambedkar’s contribution to the nation. That is, the Parliament House statue insisted upon Ambedkar’s conformity to the national agenda rather than recalled his hostility towards Hinduism, which he saw as the essence of caste. While the Constitution thus fitted Ambedkar into a secular mould, it is interesting to note that the Constitution was given a radical meaning by Dalits. As Pauline Mahar-Moller has shown in a monograph on a village in western UP, Untouchables interpreted the Constitution as a new law replacing the ‘Hindu laws of caste’ (Mahar-Moller 1958). This attempt at bringing Ambedkar within a national consensus in the name of ‘secularism’ did not prevent Ambedkarites from emphasizing their own radical understandings of Ambedkar. On the one hand, they took this official recognition as a welcome step that gave them legitimacy; on the other, they continued to publish biographies of Ambedkar and other vernacular political pamphlets in which his ideology was unfolded more uncompromisingly.

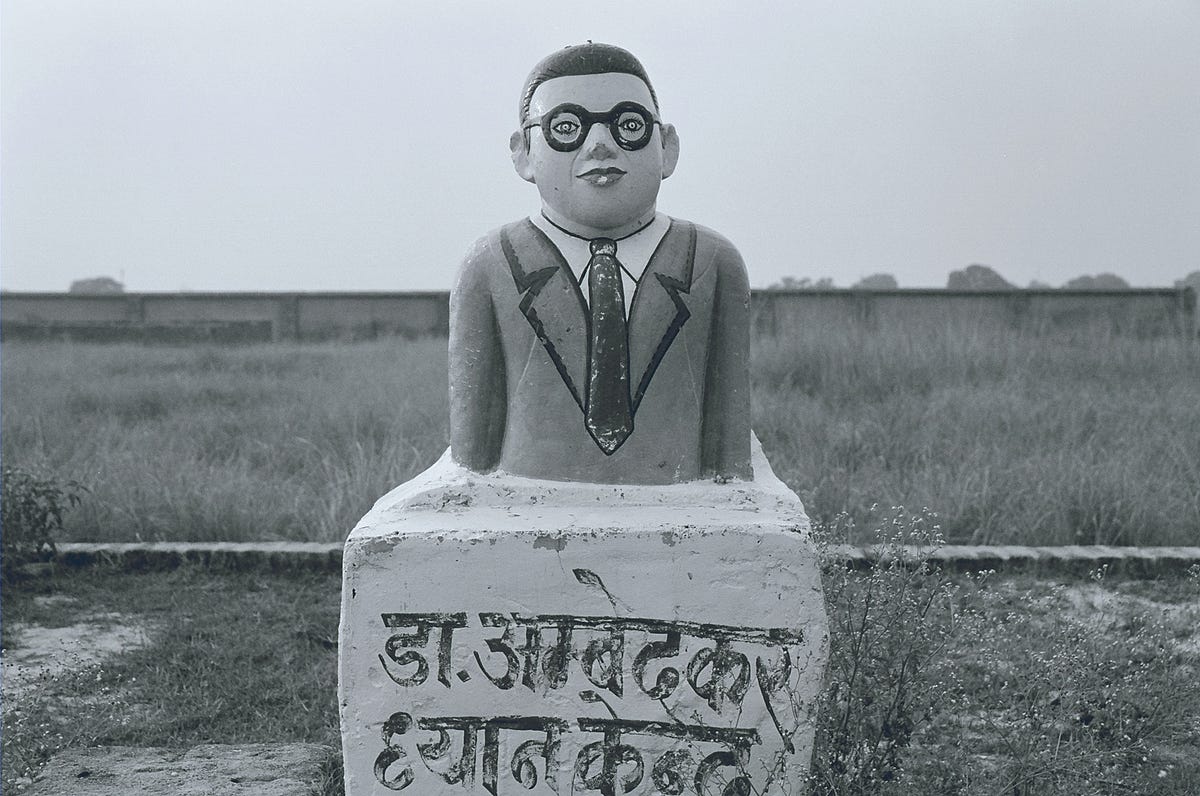

In UP, the statues recently set up tend to reproduce the iconographic pattern of the statue that stands in front of the Parliament. The official ones, set up by the provincial BSP governments since 1995, are identical, made in bronze and several metres in height. But in villages or slums as well as in roadside sculptors’ shops, one can see smaller stone models, which are painted once purchased. The ones with the upraised arm are relatively expensive (about Rs 3,000) due to the larger size of the stone used by the sculptor. Simple busts made of cement were also installed in the early 1990s, but nowadays people generally have a preference for the full-size stone model, the one with the raised arm and the Constitution. These non-official statues have a much livelier aspect: they are painted in bright colours, the three-piece suit generally light blue, the shirt white and the tiered, with occasional variations. The book is painted red and carries the inscription in the Devanagari script, ‘Bharatiya Sanvidhan’ (‘Indian Constitution’). The statue’s usual iconographic features are the three-piece suit, the tie and the pen clipped in the front pocket, that recall Ambedkar’s excellence in higher education and statesmanship; the raised arm recalls his relentless struggle and his stature as a national leader; and last but not least, the Constitution recalls his contribution as Chairman of the Constitution Committee.

The Constitution is indeed a very important feature which makes clear that Dalit struggles, despite being branded ‘communal’ by their adversaries, are for the implementation of the laws solemnly adopted by the nation. This iconographic uniformity reflects a certain popular emphasis on orthodoxy, perhaps intended to avoid misinterpretation or misappropriation of Ambedkar in a context where nationalist Hindus, trying to attract Dalits into their fold, have sought to emphasize Ambedkar’s ‘Hindu-ness’. During the BJP’s 1998 electoral meeting in Kanpur, for example, the BJP leaders paid tribute to Ambedkar by applying a coloured tika on the forehead of his portrait. Although Dalits sometimes do this too, for garlanding a portrait and applying a tika is a common way of paying tribute to someone’s memory, the Hindu nationalists did not do this innocently, using it rather as a way to root their programme of Hinduisation of Dalits in popular practice. Ambedkarite activists, however, constantly fight such practices among their own because of their ideological implications: garlands, flowers, and incense, which despite their religious connotations are not identified as exclusively ‘Hindu’ (Muslims also use them), are welcome, while tikas have become ideologically suspect. However, despite constraints such as these that enhance control over popular practices and thus create more uniformity, the village models also reflect popular creativity through various details added by the painter. For example, the shoes of a small statue in a Kanpur Dehat village had been labelled ‘Nike’ and ‘made in Japan’, locating Ambedkar’s excellence in the contemporary era by association with foreign names that sound technologically and economically advanced. Another detail contributes to the personality of the statue: probably owing to the technical difficulty of sculpting Ambedkar’s spectacles, sculptors tend to add real black plastic glasses, contributing to the cartoon-like appearance of the cheaper models. All this makes the Ambedkar statue an authentic object of popular art, with creative aspects that often assist the democratization processes.

This iconography, which represents Ambedkar as a man of international stature, rather than in traditional Indian dress (as Gandhi and other Congress leaders are represented), has attracted a wide range of critics from different political backgrounds, from Marxists to Gandhians and nationalist Hindus, all of them sharing a concern for ‘cultural authenticity’.[7] These critics generally dismiss Ambedkar’s Western dress as not genuinely Indian and/or as unfit for a leader representing the poor. Reflecting the irritation of its urban elite readers with the BSP’s symbolic politics, the Lucknow-based English daily, The Pioneer, published several indignant commentaries in its ‘Letters to the Editor’ section. One reader from Lucknow was scandalized by the official celebration of Ambedkar’s birthday under BSP rule in April 1997: a celebration lasting several days, with fireworks, a massive turnout of Dalit villagers in the state capital, and state-sponsored publicity for the BSP. This reader also pointed to the ‘injustice’ suffered by Gandhi, whose statue seemed comparatively neglected, although Ambedkar’s contribution to the nation was ‘much less’, in his opinion. The same reader emphasized that even though Ambedkar had chaired the Constitution Committee, he had not been involved in the freedom struggle and was — according to him — a convert to ‘western culture’. Coming from a reader of the English press, this judgement is somewhat puzzling. The reader’s dislike of Ambedkar, however, reaches its peak over the question of his dress — the suit supposedly epitomizing his toadying relation to the British administration: ‘In his statues he is invariably depicted wearing a three-piece suit. One not fully conversant with Indian history would, on seeing the statue, likely take it to be that of a British governor’ (The Pioneer, 15 April 1997). Such comments show the perpetuation of the Congress annoyance with Ambedkar among the English-speaking elite, who criticize Ambedkar’s assumed modernity as Western alienation, and interpret his critique of Hinduism as anti-Indian. The imposition of the ‘Untouchable’ leader’s image in public space thus creates a general feeling of intrusion and decline among the elite.

A rationalized version of this critique in the magazine India today provides a good indication of the perceptions of the managerial middle class. Titled ‘Exchequer suffers as Mayawati splurges on statues of Dalit heroes’, the article denounces Mayawati’s symbolic politics in UP, ridiculing the Ambedkar project of Lucknow, and casting aspersions on Mayawati’s intellectual ability (India today, 28 July 1997). In sum, the BSP’s politics of symbols has been criticized as a waste of money and energy that hardly benefits the poor. Whether or not such arguments emerge from genuine concern for the poor, they certainly come in handy in ridiculing their political assertion.[8]

Ambedkar’s Western dress has thus become the focus of the Westernized and non-Dalit elite’s disapproval of Dalit efforts at empowerment.[9] Such normative viewpoints, based on intellectual reconstructions of what is truly ‘indigenous’, are not reflected among Dalit villagers, who take pride in Ambedkar’s dress as symbolic of his excellence in education and statesmanship. Instead of dismissing Ambedkar on grounds of ‘cultural alienation’ or ‘false consciousness’, one should rather try to understand the way he was appropriated by Dalits and turned into a device for their assertion. The struggles to impose his statues in public places were a major contribution to this process. The following description of the manner of their initial installation in the cities, before the technique was brought to the villages, will help establish how this culture of symbolic struggle first developed.

III. Setting up statues of Ambedkar in UP: The first attempts

After the important mobilizations of the 1940s (Rawat 2003), the Ambedkarite leadership in UP was to remain at the margins of electoral politics for over four decades, with the exception of the temporary and geographically limited success of the RPI in the mid-1960s (Duncan 1979). The Scheduled Castes were the great losers in the process of land reforms, as they were generally unable to overcome administrative bias (Mendelsohn and Vicziani 1998; Thorner n.d.). Greater progress was achieved in access to higher education and to job quotas in the administration. The Chamars, representing about 60 per cent of the state’s Untouchable population (Mukherjee 1980), gradually came to comprise a sizeable section of government servants. Barred by service rules from active participation in politics, an engaged minority among the latter nevertheless continued to support Ambedkarite organizations, providing the intellectual backbone of the local Ambedkarite movement. But the movement remained confined within geographical and caste boundaries, being evident mainly in the cities of Allahabad, Kanpur, and Lucknow and their rural surroundings, as well as in the western districts of UP, and mostly (although not exclusively) based among the Chamars. In the cities, the leather industry had provided the economic foundation for the emergence of a Chamar elite after the colonial period (Gooptu 2001). Even before Independence, this elite had developed a symbolic strategy through Dalit processions in honour of untouchable Bhakti saints, like Sant Ravidas.[10]

When Ambedkar died on 6 December 1956, his followers in Kanpur took no time to organize a sok sabha (condolences assembly), using the same procession model (Bellwinkel-Schempp 2004). At village Atwa, in the adjoining rural district of Kanpur Dehat, the procession was organized on the pattern of a Hindu procession, with the icon in the palanquin simply replaced by a picture of Ambedkar. The procession was met with stone-throwing by the upper castes.[11] On 14 April 1957, functions were organized on the occasion of Ambedkar’s birthday. These two dates — 6 December and 14 April — became occasions of annual celebration, although the latter, currently known as Ambedkar Jayanti, became far more prominent.

The oldest Ambedkar statue I found in Uttar Pradesh is on the outskirts of Allahabad, by the side of the national highway. I was informed by some elderly men that it was indeed the first Ambedkar statue to be installed in Allahabad. In a house nearby, I was received by the son of the man who had installed the statue. He told me that his father had fought in the Indian army against Pakistan in 1965 and that the Harijan Kalyan Ashram, a Gandhian institution, had rewarded him for his service to the nation by giving him a piece of land, on which he built his house. He decided to install the statue by way of tribute to Ambedkar for what he had done for his community. According to the son, his father felt that he owed his position in life in some measure to Ambedkar’s struggles.

In order to collect money for the statue, he formed an Ambedkarite Committee with Scheduled Castes of the area, including villagers. The committee ordered the statue from a local artisan, who made it according to the prevalent technique — a model of straw covered with cement and painted. The statue was originally mounted on a pedestal of bricks, though it is now almost at ground level because of subsequent road works.[12] Its iconography is different from that of all the others I have seen, in that it has not been influenced by the model in front of the Parliament building in New Delhi. It is a black-and-white, life-size representation of a young Ambedkar wearing the black dress of a lawyer. His arms are by his side and he carries a book in his left hand, which could be meant to be the Constitution though it is not marked as such and is small in size.

A neighbour said that the monument had been installed at the time that Indira Gandhi took over as the All-India Congress Committee president, and before she formed the Congress(R), which places it somewhere between 1966 and 1969. The people of the committee who managed the installation were now all dead, except one, but he, unfortunately, had not attended the inauguration. However, it had been a simple function, according to this man. There was no leader, no big officer, and no plaque: just local villagers, workers from the adjoining Bumbruli glass factory, and other admirers of Ambedkar who came from the city of Allahabad. A building was now under construction for a Bauddh vihar (Buddhist shrine) behind the statue. The statue was in bad shape and I was told that it would be replaced by a new one at the inauguration of the Bauddh vihar. They would not throw this one away but reinstall it in a village. Memory was vanishing, and there would soon be no trace of what could be, if not the oldest, certainly to my knowledge one of the first attempts at installing an Ambedkar statue in Uttar Pradesh.[13]

In 1969, another initiative came from Kanpur, a major historical centre of the Ambedkarite movement in Uttar Pradesh. This one was of a different nature, however, for what the local RPI followers intended was not just to pay their private homage to their leader, but also to gain some official recognition. They had been inspired by the statue set up at the National Parliament building and wanted one erected in their city. They made a collection among the local Ambedkarites and ordered a statue after the Parliament model. It was made of cement and painted white. Their plan was to have it installed on 14 April (Ambedkar Jayanti) on the main road at the Motijheel gate of Kanpur municipality. Having failed to get the authorization from the district authorities even after several requests, the RPI leaders assembled a crowd on 20 April in a nearby park. The demonstrators marched in procession towards the Motijheel gate with the statue on a cycle-rickshaw, intending to install it even without permission.[14] They shouted slogans threatening to destroy Nehru and Gandhi statues if the local authorities did not allow them to instate the Ambedkar statue. The police charged with lathis, while the crowd, now led by Dalit youngsters, hit back at them with bricks they found lying by the roadside.[15] In the pitched battle, more than thirty people were injured, including policemen, and there were thirty-eight arrests, among them eight RPI leaders.[16] The statue, which had been dropped during the fight, breaking its arm, was seized by the police.[17] This event was reported by the press and created a shock among local Dalits. Even Dalit Congress Party supporters, who in their majority did not recognize Ambedkar as their leader, had the impression that this confrontation was mainly on account of Ambedkar’s caste, which made him unfit for public honours in the eyes of the ruling class. The Congress Party, although it claimed to follow Gandhian ideals, thus gave the impression that it refused to honour the maker of the Constitution simply because he was an ‘Untouchable’. Although the attempt to install the statue failed, it was successful in opening a breach in Congress rhetoric by highlighting the authorities’ ambivalence towards Ambedkar and the Scheduled Castes and exposing the casteism that lay behind official secularism.

The changed political context of UP in the late 1960s and early 1970s brought more conducive political conditions for the Congress Dalit leadership, who had until then been relegated to subaltern positions within the ruling party. To compensate for the departure of the north Indian intermediary castes from her party’s fold, Indira Gandhi sought the support of the Scheduled Castes by nominating the Untouchable minister Jagjivan Ram President of the All-India Congress Committee. The RPI leadership from Uttar Pradesh was thus co-opted by the Congress(I). This revived the Scheduled Caste leadership within the Congress, and Untouchable lobbies within the local Party units began to assert themselves by taking up the symbolic issue of Ambedkar.[18]

The political conditions at the regional level were thus ripe for re-examining Ambedkar’s contribution to the nation. The celebration of the silver jubilee of Independence in 1972 provided the occasion. In Lucknow, the Congress Mayor, Dauji Gupta (an OBC whose father had been associated with Ambedkar), decided to install statues of Ambedkar and of the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia (1910–67). The project was approved by most of the Congress municipal corporators (barring a few Muslims with Zamindar backgrounds) and the Socialist Party, but opposed by the Jan Sangh.[19] The life-size stone statue of Ambedkar was ordered from Jaipur (a city renowned for stone sculpture), painted in white, and officially unveiled on 14 April 1973 at the Hazratganj crossing, a prestigious and central location, just across from the Gandhi monument. As on every 14 April, a procession of the Scheduled Castes converged on Hazratganj. The chief guest was a Buddhist monk from Malaysia, who opened the function with incantations in Pali. The Mayor thereafter made his speech. He described Ambedkar as a man whose talent was such that he had been able to overcome the obstacle of untouchability and even become the chief architect of the Constitution. He added that, even though Ambedkar had converted to Buddhism, there was no difference between Buddhism and Hinduism, as the Buddha was known as an incarnation of Krishna. His speech thus emphasized Ambedkar’s acceptability within a secular framework, a gesture which may be seen less as an attempt to dilute Ambedkar’s radicalism than as a strategy to have him acknowledged among the nation-builders. It was, nevertheless, in complete contradiction to Ambedkar’s explicit insistence, made clear during his public conversion, that Buddhism could not be equated with Hinduism and that the Buddha might not be treated as one of the avatars of Vishnu (Jaffrelot 2005). Reiterating the Gandhian benevolent approach towards untouchability, the Mayor also asked the high castes to take a vow to fight untouchability, arguing that it was this that hampered the nation’s progress. Urging society to give ‘Harijans’ a better deal so that they could fully contribute to the building of a socialist society, he also expressed his wish that the government declare 14 April a national holiday. The news article mentions that Ambedkarite leaders and writers such as Lalaï ‘Periyar’ Singh Yadav from Kanpur (popularly known as the ‘north Indian Periyar’) subsequently made speeches. We can expect those speeches to have been more radical in their content, especially in their critique of Hinduism, but these are not reported in the article (The Pioneer, 15 April 1973) and the Mayor’s version was the only one to appear. This in itself is indicative of the interpretation of Ambedkar followed by the media (i.e., the official one). In my interview with him, the ex-mayor, Dauji Gupta, told me that the question of interpretation was not an issue for him: the statue’s meaning was to be found in Ambedkar’s writings and his life of struggle. Official recognition was an encouragement to read this literature.[20]

Gupta’s assessment of the importance of official recognition was also echoed by the Ambedkarites who, having been marginalized after Independence, sought official recognition through such events. The problems in the official interpretation were secondary for them. Ambedkarites indeed gained legitimacy within their own Scheduled Caste circles through the recognition of their symbol, and it became easier for them to speak ‘the’ truth about Ambedkar and his struggles against the Congress once the statue was formally installed and Ambedkar was no longer officially portrayed as ‘communal’ and ‘seditious’.

The official statue that was inaugurated in Kanpur a few months later confirms this impression. Although Ambedkar was reinterpreted in a way that fitted the Congress Party’s ideological framework and political interests, the activists did not contest such dilutions of their radical leader’s ideology. But thereafter they fully re-appropriated the monument, imparting to it their own radical interpretations. The process that led to the installation of this statue needs to be narrated. Scheduled Caste municipal corporators across party lines had formed a group to pressurize the municipal council to add the name of Ambedkar to a list of national heroes whose statues were to be commissioned on the occasion of the silver jubilee of Indian independence. Shiv Prasad Bharti, a Scheduled Caste municipal councillor belonging to the Congress, was prominent in this move. Though not an Ambedkarite himself, the repression faced by RPI activists for the installation of the statue at Motijheel in 1969 had shocked him into asking himself what, apart from untouchability, was the real obstacle in acknowledging Ambedkar’s contribution to the nation (Bharti 1985). The Chief Officer (Mukh Adhikari) of Kanpur Municipality, himself Scheduled Caste from south India and an Ambedkarite, allotted the monument a site behind the gate of Nana Rao Park. This park had been the scene of dramatic events during the 1857 mutiny and was therefore locally regarded as a very prestigious site.

The organizers brought the statue from Jaipur and managed to get Defence Minister Jagjivan Ram to unveil it, on 30 June 1973. The life-size statue mounted on a tall marble pedestal represents Ambedkar dressed in a blue achkan, with his two hands resting on a walking stick, but without the Constitution. Ambedkar wore this dress (of the type associated with Nehru in the popular imagery) when he became independent India’s first Law Minister. It recalls the image of him handing over the Constitution to Nehru and Rajendra Prasad that is widely circulated as a chromolithographed poster. This iconographic representation was a reminder of Ambedkar’s reconciliation with the Congress (though it was brief and partial), and his wisdom and respectability (old age signified by the walking stick), rather than his role as a radical leader of the Scheduled Castes. A local Jan Sangh Scheduled Caste politician (belonging to the Bhangi caste) was sent by his party to create some opposition. He was arrested by the police when he took out his black handkerchief. According to my Dalit informants, Jagjivan Ram said in his speech that Ambedkar had drawn the sketch of ‘Untouchable uplift’ (Achutudhar) which, as a central minister, he had himself filled with colour. He thus presented himself as heir to Ambedkar’s legacy, despite the fact that he had been pitted against Ambedkar by the Congress after the second Round Table Conference. When Ambedkar declared his conversion project in 1936, Jagjivan Ram had even publicly called him a coward who could not lead his people, a statement which Ambedkarites criticized as a sign of his political alienation (Das n.d.).

Some activists who were present at the unveiling ceremony boasted of raising objections during the speech, but others who were also present deny that any such incidents took place. Though many Ambedkarites in the audience may have disapproved of Jagjivan Ram’s speech, it seems that they took it quite seriously, for all of those whom I met remembered in detail what the Scheduled Caste minister had said on the occasion. One of them could even repeat passages he had learnt by heart.[21] What seems to count the most for Ambedkar’s admirers is that their leader’s public image was symbolically rehabilitated through this official ceremony. This inauguration thus gave Kanpur’s local Ambedkarite movement its monument, which continues to be cherished today as the focal site of Ambedkar’s yearly Ambedkar Jayanti celebrations.

The event actually set up a fashion in Kanpur, where two other official Ambedkar statues were inaugurated by local politicians — the first in 1978 by G.D. Tapase, a Scheduled Caste governor nominated by the Janata Party, and the second in 1983 by Mohammad Arif Khan, a Congress Central minister, in the Gudar Basti slum. It is interesting to note that, just as the installation of Hanuman statues or Sufi saints’ graves had been used since the colonial period by slum dwellers to avoid expropriation, the construction of this small Ambedkar park in the long and narrow slum was part of a strategy to counter an expropriation move by the North Indian Railways, on whose former tracks it had grown.[22] The initiative for erecting these statues was taken by Ambedkarite committees composed of educated unemployed youths and government servants, for whom the organization of such events brought prestige and status in the Dalit community. By inviting such prestigious guests of honour, these educated youngsters were able to build and display social capital through the official connections now available to them. Unveiling ceremonies for Ambedkar statues were thus the occasion to build their networks within the administration and political parties.

None of those new statues would, however, match the prestige of the Nanarao Park monument, where Ambedkar processions started converging each year on 14 April. The importance attached to this site combines at least three features: (i) in the light of the 1969 struggle, this installation was a victory, even a symbolic revenge over the administration; (ii) it had a prestigious location and was unveiled by a central minister; and (iii) it represented the achievement of unity by all the Scheduled Caste leaders, whatever their party affiliations. Ambedkar thus stood symbolically as the unifier of Dalits, and through unity their collective status within the nation could be enhanced.

IV. Dalit Panther militancy: Keeping watch on the symbol

In the late 1970s the expansion of education resulted in educated unemployment, which sustained political radicalism among the educated youth of all groups, including Dalits. The countryside of Uttar Pradesh witnessed growing tensions because of the failure of the land redistribution policies that were supposed to have been implemented under Indira Gandhi’s Twenty Points scheme against poverty (1976) but which proved ineffective in face of the inertia of the local administration. The Janata Party government in UP during 1977–80 promoted middle peasant interests and totally neglected the Twenty Point scheme and the interests of the rural poor (Kohli 1987). Rising atrocities against Scheduled Castes were generally provoked by the assertive behaviour of this new generation of educated Dalits who openly defied caste hierarchies. Their assertive attitudes not only worried upper-caste employers who relied on a submissive labour workforce, but also irritated upper-caste youths, who faced unemployment problems and blamed their fate on the quotas in favour of the Scheduled Castes. Conflicts surfaced on symbolic matters, like objections to their wearing neat shirts and trousers.[23] The previous generations used to wear ragged clothes, either because of poverty or because they needed to appear subservient to the upper castes, often for both reasons.[24] In the traditional village economy, old clothes were offered to them by the upper castes in exchange for their services, as were food leftovers. By refusing this degrading custom of jhutha, and by wearing good clothes, the new generation thus contested the caste inferiority imposed on them. Caste/class tension became palpable in everyday life, with conflicts often crystallizing around issues of honour. The Ambedkar icon, symbolizing Dalit pride, became a way to play out such assertions publicly.

On 14 April 1978 in Agra, the Ambedkar Jayanti procession of the Jatavs (Chamars), which carried an Ambedkar statue on an elephant, was attacked while passing through an upper-caste neighbourhood. The upper castes used the riot that followed as a pretext to persuade the administration to change the route of the yearly Dalit procession. In reaction to the administration’s acquiescence, the Jatavs attacked government buildings and confronted the high castes and the police, leading to hundreds of arrests and ten deaths. Peace was restored only when the army intervened and when the administration satisfied the demands of the Scheduled Castes (Lynch 1981).

The new militant Scheduled Caste (hereafter ‘Dalit’) youth in Uttar Pradesh found an outlet in the Dalit Panther movement, which had achieved nationwide recognition during the mobilisation for renaming the Aurangabad university after Ambedkar in 1979. The violent police repression (five deaths in Nagpur) attracted considerable media attention and deeply impressed educated Dalits. A ‘Long March’ in which Ambedkarites from all over India participated was held in December 1979 (Murugkar 1991). Local branches of the Bharatiya Dalit Panthers were thereafter established in the cities of Uttar Pradesh and other states of north India.

In Kanpur, the first Dalit Panther meeting took place in Nanarao Park in April 1981 — significantly, at the site of the Ambedkar statue which had been inaugurated by Jagjivan Ram eight years earlier. The local Dalit Panther leader was Rahulan Ambavadekar, a Chamar and the son of a bus driver. Raised in a labour colony, he had done his MA in political science and was completing his LLB at Aligarh Muslim University where he was a student of B.P. Maurya, the firebrand RPI leader. Soon after the inaugural meeting, a symbolic assault on Ambedkar gave him the occasion to assert the Dalit Panthers’ strength publicly. On 23 April 1981, as the Dalits of Gadarian Purwa (a locality of Kanpur) were celebrating Ambedkar Jayanti, a drunken Brahmin police sub-inspector and his constables disrupted the meeting and kicked the Ambedkar portrait. Those who protested the insult were beaten up by the constables, while the sub-inspector threatened the public at gunpoint.[25] A protest meeting of the different Chamar sub-castes was called, led by the Dalit Panthers. Rahulan wrote a leaflet demanding the immediate dismissal of the guilty policemen. A procession through the city was organized on 3 May, attracting a crowd of 50,000 people according to the national press (Bhu Bharti, September 1981). Such an angry crowd on the streets of Kanpur in an already tense industrial context was perceived as a threat by the local administration. The guilty policemen were arrested and imprisoned to defuse the tension, though they were released without sentence soon after. The Dalit Panthers protested by printing a leaflet, which was distributed in Dalit bastis and sent to the provincial and central authorities. They demanded nationalization of all industries and agricultural land, besides certain symbolic demands. The first of their fourteen demands was that Kanpur district should be renamed ‘Ambedkar Nagar’; the third concerned the erection of a statue of Swami Achhutanand, the ‘Untouchable’ leader of the early Adi Hindu movement; and the eighth concerned the renaming of Marathwada University after Ambedkar (Bharatiya Dalit Panthers n.d.). Symbolic claims were thus given equal footing with material ones. Symbolic assertion had become a major feature of Dalit political culture, and the political efficacy of such skills was soon to be demonstrated.

V. The ‘mushrooming’ of Ambedkar statues in villages

The 1980s saw Ambedkarite mobilizations reach areas where the RPI and the Dalit Panthers had previously had little if any impact. Government employees were organized by Kanshi Ram through the Backward and Minorities Caste Employees Federation (BAMCEF) and directed to spread knowledge of Ambedkar in villages.[26] In Kanpur, for example, many Dalit workers had kept in contact with their villages in eastern UP.

They calculatedly attended weddings in their caste circles to talk about Kanshi Ram and his goal of building a political party that would snatch power from the Congress. Early campaigns of the BAMCEF relied partly on kinship networks as well as on personal contacts with co-workers and other educated Dalits.[27] After the formation of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in 1984, the activists became more systematic and started moving out to villages around Kanpur on weekends to incite educated Dalits, teachers and students for instance, to set up Ambedkarite committees.[28] A majority of these Dalit villagers had never heard of Ambedkar, or were at least not conscious that he was ‘one of us’. Setting up Ambedkar statues, motivating fellow villagers to attend the party’s mass meetings and acting as the party’s electoral agents in the polling booths were among the tasks taken up by the Ambedkarite village committees. The iconography of the Ambedkar statues, with the two pens in the front pocket of the suit and the book, was an easy object of identification for educated Dalits. The pen clipped in the shirt’s pocket was characteristic of their way of dressing, proclaiming their education and claims to social status in a modern world. The icon was a suitable pedagogic tool to convey Ambedkar’s message to their uneducated Dalit brethren.

Even though Chamars dominated the Ambedkar committees, the criterion for participation was the level of education, rather than belonging to this particular caste. The main difference from other Dalit castes was that the Chamar activists managed to assert their leadership over their caste. The committees included individuals from all the Scheduled Castes as well as OBCs but, compared to other castes, the Chamar population participated en bloc. This was for several interrelated reasons: (i) the Chamars had a record of Ambedkarite leadership and an Ambedkarite culture had already grown among them in cities and even in certain rural areas; (ii) Kanshi Ram was himself a Chamar; and (iii) they had become more involved in education and had therefore produced more government employees than the other Scheduled Castes. This of course had a direct impact on their early involvement with Kanshi Ram through the BAMCEF, but the other factors also contributed to facilitating the spread of the idea that the Ambedkarite culture was a part of their social and political identity, even though they had mostly voted for the Congress and earlier considered Gandhi a well-wisher.

Setting up an Ambedkar statue in a village was a highly controversial and delicate task. When and wherever it happened, it provided the Ambedkarite village committee with credibility. Celebrating the value of education, Ambedkar gave legitimacy to the social and political ambitions of those radical young men from the Scheduled Castes. The inaugurations, mimicking official unveiling ceremonies, highlighted their authority. The symbolic control of the village’s public space was a daring assertion, which the upper castes perceived as a threat, even an insult, often provoking confrontations, and sometimes even the destruction of the statue. Even if it could lead to bitterness and conflict, one of the major positive achievements as far as political mobilization was concerned was the Dalit unity created around the symbol.

In 1990, a portrait of Ambedkar was installed in the Central Hall of the National Parliament building by the V.P. Singh government. This event had wide repercussions and gave a fresh impetus to Dalit symbolic mobilizations. The year 1991 was celebrated as the Ambedkar centenary at the national level, thus providing official legitimacy to the Ambedkarites. Ambedkar statues were set up by Ambedkarite committees in many remote places. BSP activists cashed in on such symbolic activities to sustain mobilizations, organize public meetings and win visibility in the local newspapers. For example, one BSP committee in a Kanpur slum installed a board renaming the slum ‘Ambedkar Nagar’ and built a pedestal for a statue. Both were destroyed by gundas hired by the local MLA. The BSP district cell then organized a one-week dharna in front of the Kanpur kachehri (administrative centre), the ward committees taking turns to lead the protest on successive days. In villages, material demands were integrated with symbolic politics. The focus was on implementing effective ownership of the communal plots of land that had been promised to landless labourers by the Indira Gandhi government. BSP workers organized cycle processions from village to village with shouted slogans such as: ‘Jo zameen sarkari hai, wo zameen hamari hai!’ (The government land belongs to us!), and ‘CM–PM vote se lenge, SP–DM arakshan se lenge!’ (We’ll take the offices of Chief Minister and Prime Minister with our votes, we’ll take the offices of Superintendent of Police and District Magistrate with our reservations!)[29] What these slogans have in common is their emphasis on the conquest of public space, from the concrete demand for land to the metaphor of the political conquest of state authority. It was common knowledge that anti-poverty measures had failed, largely because of upper-caste hegemony within the administration and lack of political commitment to social change. Therefore, what was needed was the empowerment of Dalits to make the administration deliver on its failed redistributive measures. Dalit villagers found a more direct manner to link the political symbol with economic demands that were omitted from the BSP agenda for tactical reasons. In many instances, Ambedkar statues were erected on communal village land (gaon sabha zameen), which was supposed to have been redistributed to the landless in the Twenty Points Programme against poverty launched by Indira Gandhi in 1976, when land titles for some 1 million acres were distributed in Uttar Pradesh.[30] The symbol was all the more appropriate and meaningful as the constitution held by Ambedkar emphasized the legality of the claim. The concrete demand for the due plots of land could thus be extended to a demand for all the democratic rights that the Constitution stood for, but which remained on paper. The statue thus stood as an incentive for democratic mobilization and became a remarkable tool for the pedagogy of the oppressed.

The Ambedkar statue phenomenon literally exploded after the SP– BSP coalition came to power in Uttar Pradesh in December 1993. The year 1994 was marked by an unprecedented number of ‘Ambedkar statue incidents’ (Ambedkar murti ghatna) reported by the press (Jaffrelot 1998).

The most impressive was the Shergarhi incident, in the urbanizing outskirts of Meerut in western UP, where Dalits installed an Ambedkar bust in a public park that had been targeted by Meerut’s Housing Development Corporation for new (albeit illegal) middle-class housing construction.

As Ambedkar is associated with the Constitution, his statue stood as a reminder of legality, but it also conveyed the threat of a ‘communal’ symbol in a tense situation — touch it, and the whole community will become frenzied. The next morning, as the police reached the village to remove the unauthorized statue, heated arguments between Dalits, the police and the representatives of the Corporation began degenerating into violence. Police constables were beaten up by some Dalits and two of them even suffered bullet injuries. The police fired at the crowd, destroyed the statue and attacked Dalit houses. Two Dalits died and thirty were injured, according to official records. Next day, another Dalit life was lost in a new episode of police firing. Dalits of the whole district then mobilized to defy the curfew orders (Pai 2002) and 600 persons were arrested.[31] Preferring to preserve its alliance within the Uttar Pradesh government rather than side with the Dalits, the BSP failed to support the victims and, ironically, even Mayawati dismissed the installation of the Ambedkar statue as ‘unnecessary’. Ultimately, other incidents of violence, mostly pitting OBC farmers (the bulk of the SP’s electoral supporters) against Dalits, put a strain on the SP–BSP alliance, which finally broke in June 1995.

VI. Mayawati’s symbolic politics and its rural impact

Immediately after the fall of the SP–BSP coalition government, the first BSP-led government came to power, thanks to a tactical agreement with the BJP. Mayawati became the state’s first Dalit Chief Minister. Her politics focused mainly on the posting of Dalit administrators in positions of authority, on the selective development of villages with large Dalit concentrations (‘Ambedkar villages’) and on a symbolic programme of ‘Ambedkarization’ of Uttar Pradesh. The latter can be summed up as the installation of outsize Ambedkar statues and the renaming of districts and universities, as well as the construction of fancy public parks named after Dalitbahujan (i.e., non–upper caste) personalities.[32] An immense Ambedkar park was even constructed in the state capital Lucknow, adjoining the Taj Hotel construction site. The criterion for the size of the Ambedkar statue was that it should be higher than the dome of the five-star hotel under construction. Both projects involved official corruption, which was highlighted by the national media as well as by the opposition parties. Even though the more intellectual Ambedkarite circles dislike her unrefined attitude and language, Mayawati’s popularity with Dalits and her authoritarian personality has become a symbol of Dalit assertion. During her second term as Chief Minister (March–September 1997, once again thanks to BJP support), she gave official recognition to her party workers’ earlier practice of setting up statues in villages.

Thus, not only has a typically official practice (the installation of statues) been appropriated by activists, but the reverse is also the case: the government itself adopted and made official an earlier practice of the BSP workers. The process of state-society influence has very clearly become circular in this case. A Government Order assigned half an acre of communal land in each village for the construction of an ‘Ambedkar Park’. The main practical difference from the former attempts of the village committees to erect Ambedkar statues was that it was now necessary to obtain an authorization from the District administration to do so. Installing a statue now required the acquisition of administrative knowledge.

Despite the fact that the Mayawati governments lasted barely six months each, they made some difference to the Dalits through the enforcement of laws in their favour (Mendelsohn and Vicziani 1998). During her public meetings, Mayawati warned local administrations to pay special attention to her party activists’ demands.[33] A Government Order directed the district police administration to give special attention to complaints falling under the category of the Untouchability Offences Act. Local Dalit activists were instrumental in bringing these complaints to the attention of the administration, as also demands for state bank loans, public distribution licences, etc., improving the lot of the poor as well as consolidating the economic status of relatively better-off Dalit families. There were even cases of local BSP cells organising protest demonstrations (dharnas) to dislodge reluctant administrative officers.[34] Sanctions from higher authorities were therefore engineered from below, countering the administrative blindness to Dalit problems that had long been the unofficial law of the land.

Mayawati’s politics in favour of the poor did not go as far as a general land redistribution to land-title holders. However, her official move to develop Ambedkar parks in villages was perceived as a potential threat by those dominant castes who indulged in illegal cultivation of this ‘surplus’ communal land, leading to conflicts. As in previous cases, the Ambedkar statues were still the focus of contention. I will relate one example from Kanpur Dehat district. Balahpara Karan is a huge village (about 25,000 inhabitants according to the 1991 Census) where the overwhelming majority of Dalits are landless and work on daily wages for upper-caste farmers. Many of the latter have bypassed land-ceiling laws (up to six times for the largest property), which restrict the individual possession of land to 40 acres. Landless families hold official documents (pattas) giving them the right to take possession of small parcels of the ‘surplus land’ meant for redistribution, up to a total of 200 acres for the whole village. In 1995, the night after the Ambedkar statue was set up in the village, the upper castes broke its cement base, leaving the statue lying on the ground. Dhaniram Panther, the local Dalit Panther leader, rushed to the scene with the police, in whose presence the statue was reinstalled. Police constables camped in the village for several months to protect the monument.[35]

The implementation of the official programme for Ambedkar parks involved politicking at the village council level, and instigated conflicts. The cases I reviewed in Kanpur Dehat tend to show that such parks could only be set up where Dalits were in large numbers and where they were able to gather some support from OBCs. This can be explained by the fact that the signature of the head of the village council was needed before the demand could be submitted to the District Magistrate. The Dalits would sometimes fall short of a majority, generally because one or two Dalit council members had joined the opposite faction. These conflicts sparked tension and even violence in many cases, sometimes leading to cycles of murder and revenge. This happened for instance in Rudauli village,[36] which was selected as an ‘Ambedkar village’ by the BSP government in 1997.

Rudauli was entangled in a bitter conflict over communal land with the Yadavs, a powerful OBC community, which degenerated into caste violence. A Yadav sought to encroach on some communal land located at his doorstep by constructing a wall around it. The local Ambedkarite committee, whose members were mostly unemployed educated young men, reacted by destroying the wall and building a pedestal for the installation of the Ambedkar statue, on which they wrote ‘Jay Bheem’, the Ambedkarite call for victory. The Yadavs then called in a group of armed gundas who began terrorizing the Dalits. But a crowd of Dalit villagers, including women, suddenly attacked the Yadav gundas with stones, home-made bombs, and sticks, and managed to chase them away. The next morning, two of the gundas, dressed in saris, were caught in a field while they were trying to escape after having spent the night hidden with some relatives. One was beaten almost to death by the crowd and the other, identified by Dalit women as a rapist, had his arms chopped off with an axe. The police were called and rescued the victims in an unconscious state, though both eventually survived. The Dalits maintain that this incident had a positive impact. Rajesh, one of the BSP activists, said: ‘The people realized that those Scheduled Castes are dangerous and that they have political connections. They are willing and able and they will not give up the fight, come what may.’[37]

To these villagers, installing a statue was a daring act that cashed in on the new power equation. It gave shape to their new status, enacting a political change that would otherwise remain beyond the realm of the local reality. This understanding contrasts with the earlier experience of village inertia, where the social change witnessed by the outside world stopped at the doorstep of the rural world. Like the Constitution, political change needs to be performed here and now, while the government is favourable; otherwise it can vanish like a missed opportunity. Establishing the statue makes the point that the democratic coup de force of the BSP governments has affected the balance of power in the village as well. The symbol thus links wider political struggles to local issues, emphasizing that Dalit progress requires a relentless struggle at every level. Wherever the Ambedkar statue has been installed, Dalits have felt encouraged by this tangible symbol of success. When interviewed about the statue’s meaning, politically aware Dalit villagers in Rudauli recalled their great man’s message: ‘Educate, Organise, Struggle’. While the educated or even self-taught activists could speak at length on Ambedkar’s life and his ideal of a casteless society in India, others, politically less articulate, like a Dalit woman whom I interviewed, simply recalled that ‘he was our messiah; whatever progress we achieved, it was he who gave it to us.’[38]

After the 1999 national elections returned a BSP Member of Parliament from the Ghatampur constituency (one of Kanpur Dehat’s two national constituencies), his BSP supporters in Rudauli planned to have their Ambedkar statue finally installed and officially unveiled by him. Rajesh, the BSP activist already quoted, explained that voting was not enough and that organizing an official unveiling ceremony could do wonders by attracting a Member of Parliament to the village:

Voting should not be considered as sufficient on our part. We want our Member of Parliament to pay a visit to our village now that he has been elected. His visit will only be possible once we have organized an official programme in the village [emphasis mine]. This will have a great impact. People will realize that we are directly linked to the Member of Parliament and that we can get development works done through him. The villagers know how to give their vote, but they also know how to get an MP to act for them.[39]

As Rajesh Ambedkar indicated, official occasions like an unveiling ceremony in the village are used as a technique for building official support. In the Ambedkarite meetings that they organize, the local activists are keen on inviting prestigious Dalit chief guests. The best option for them is to have a Dalit officer, whether from the IAS (civil service) or the IPS (police), or some Dalit politician of high standing. As we have seen in connection with the unveiling ceremonies in Kanpur in the late 1970s, meetings involving high-ranking guests help the local Dalit community to publicly display its administrative connections. The meetings start with flower tributes to the statue/portrait of Ambedkar. In such events, mimicking state rituals, the Dalit elite are induced to perform an act of symbolic allegiance assuring the community of their support. Dalits are thereby assured of benefactors within the administration. These imitations of official ceremonies are therefore a crucial step in the process of empowerment (Jaoul n.d.), showing how such symbols can be used by grassroots activists to involve the subaltern elite. These ceremonies give some special standing to the Dalit elites as ‘great men’ within the community. This involves some degree of flattery, by portraying these elites as successful and committed members of the community whose support and guidance is sought by the unprivileged majority. Ambedkar’s symbol plays a very important part in this: his commitment to the community, alongside his own personal achievements, is opposed to the example of selfish Dalits who distanced themselves from their Dalit origins once they became successful. When he addressed the relatively privileged Dalit government servants, Kanshi Ram thus convincingly turned Ambedkar into a model of moral virtue, which, according to him, could help to bring together social mobility and political involvement on behalf of those caste brethren who were ‘left behind’ (Ram 1982).

It can be argued that these ceremonies provide an audience for the Dalit administrative elites, helping them to establish their patronage over the subaltern community. The replication of official gestures and speeches on such occasions unmistakably points to the influence of state culture on popular culture. But instead of seeing things only from the elite angle, there is a need to acknowledge these popular initiatives by considering them from the popular angle as well. Through the manipulation of the symbol, the local activists manage to engineer such support from the elite. Their symbolic skills testify to a new grassroots ability to take advantage of democratic institutions.

VII. Conclusion

The symbolic skills learned in the process of erecting Ambedkar statues in UP have been shaped through struggles for the symbolic appropriation of public spaces.[40] An image of conquest has pedagogically demonstrated how democratic ideals can be achieved and implemented. In the process, Ambedkar’s image can even be said to have become ‘untouchable’, but this is so in a very positive sense from which there can now be no retreat.

In spite of the negative and brutal experience of the state among the poor (Mendelsohn and Vicziani 1998), popular representations of Ambedkar have sustained a popular image of the state that renews aspirations towards it. The BSP’s rise to power in Uttar Pradesh has made the state appear as the ally of the deprived, demonstrating new possibilities and unleashing new hopes. Though the change of perception of the state should not be overstated, and deeply-rooted negative perceptions continue to be prevalent among the unprivileged, what seems to have emerged is greater ambivalence in an already complex, almost schizophrenic, popular relationship with the Indian state. The positive shift is clearly apparent in the meanings associated with the Ambedkar statues by those who mobilize around them. To Dalit villagers, whose rights and dignity have been regularly violated, setting up the statue of a Dalit statesman wearing a red tie and carrying the Constitution involves dignity, pride in emancipated citizenship and a practical acknowledgement of the extent to which the enforcement of laws could positively change their lives. As E. Zelliot has pointed out, it testifies to ‘a belief that somehow or someday the Government of India — the democracy in which Ambedkar never lost faith — will protect their rights’ (Zelliot 2001). A political message based on a positive understanding of the state has thus induced the deprived sections who have long remained at the margins of citizenship to sharpen their political skills. The relevance of this political work as far as nation-building is concerned needs to be noted. Wherever they are found, but especially in the slums and villages where they have proliferated since the 1990s, the Ambedkar statues testify to a rising consciousness of constitutional rights among the unprivileged, and sometimes even to their ability to motivate local authorities to enforce them. Such popular monuments are a tangible sign of ‘the process of social adjustment to the state’ (O’Brien 2003: 29), whereby the state becomes imagined by the popular mind, and even to some extent ‘tamed’ as a result.

It is nevertheless true that the Ambedkarite symbolic politics have reached a stage of saturation, suggesting the difficulties in the way of the contemporary Dalit movement taking up new challenges in the context of liberalization. Class differentiation among Dalits now stands as the big issue. While symbolic politics have played a significant part in democratization, today this seems a convenient motive for the Dalit middle-class leadership to push issues of class under the carpet and to talk exclusively about issues of dignity. The question remains as to how long a movement that emphasizes the dignity of the oppressed can escape material questions.

In fact, the symbolic struggles of Dalits do carry with them an underlying class dynamic. In the rural context, the statue has unmistakably fuelled class tensions between the marginal and landless peasants and the dominant castes/classes. These have reached a point where the slightest incident of disrespect towards an Ambedkar statue can easily turn into a bitter confrontation. This potential for violence itself speaks of the frustrations of deprived Dalits and their growing anger which, despite the political progress that has come about recently, inevitably accompanies their politicization.

REFERENCES

AMBEDKAR, B.R. 1945. What Congress and Gandhiji have done to the Untouchables. Bombay: Thacker and Co.

ANDERSON, BENEDICT. 1983. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

BELLWINKEL-SCHEMPP, MAREN. 2002. The Kabir panthis in Kanpur. In Monika Horstmann, ed., Images of Kabir. New Delhi: Manohar.

— — — . 2004. Roots of Ambedkar Buddhism in Kanpur. In Johannes Beltz and Surendra Jondhale, eds., Reconstructing the world: Dr Ambedkar and Buddhism in India, pp. 221–44. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

DAS, BHAGWAN, ed. 2002 [1963]. Thus spoke Ambedkar, vol. 1 (Selected speeches of Dr B.R. Ambedkar). Lucknow: Dalit Today Prakashan.

— — — . n.d. History of the conversion movement launched by Dr Babasaheb B.R. Ambedkar on October 13, 1935 at Yeola, Bombay. In Bhagwan Das, ed., Thus Spoke Ambedkar, vol. 4, ‘On renunciation of Hinduism and conversion of Untouchables.’

Bangalore: Ambedkar Sahithya Prakashana.

DAYAL, HARMOHAN. n.d. Varn vyavastha aur Kureel vansh. Lucknow: Mudrak Paigam Printers.

DUNCAN, R.I. 1979. Levels, the communication of programmes and sectional strategies in Indian politics, with reference to the Bharatiya Kranti Dal and the Republican Party of India in Uttar Pradesh and Aligarh District (Uttar Pradesh). Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Sussex.

FULLER, C.J. and J. HARRIS. 2000. For an anthropology of the modern Indian state. In

C.J. Fuller and V. Bénéï, eds., The everyday state and society in modern India, pp. 1–30. New Delhi: Social Science Press.

GOOPTU, NANDINI. 2001. The politics of the urban poor in early twentieth century India.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

JAFFRELOT, CHRISTOPHE. 1998. The Bahujan Samaj Party in north India: No longer just a Dalit Party? Comparative studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 18, 1: 35–51.

— — — . 2005. Dr Ambedkar and untouchability: Analysing and fighting caste. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

JAOUL, NICOLAS. n.d. Dalit empowerment, ‘non-political’ Ambedkarites, and the BSP. A division of political labour? In Sudha Pai, ed., UP in the nineties and beyond: Issues and challenges. Forthcoming.

— — — . Forthcoming. Dalit processions: Street politics and democratization in India. In D. Cruise O’Brien and J. Strauss, Staging politics in Asia and Africa. London: I.B. Tauris.

JIGYASU, CHANDRIKA PRASAD. n.d. Shri l08 Swami Achhutanand Harihar. Lucknow: n.p. KHILNANI, SUNIL. 1997. The idea of India. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

KOHLI, ATUL. 1987. Uttar Pradesh: Political fragmentation, middle peasant dominance, and the neglect of reforms. In Atul Kohli, The state and poverty in India: The politics of reforms, pp. 189–222. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LYNCH, OWEN M. 1981. Rioting as rational action: An interpretation of the April 1978 riots in Agra. Economic and political weekly 16, 48: 1951–56.

MAHAR-MOLLER, PAULINE. 1958. Changing caste ideology in a north Indian village. Journal of social issues 14, 4: 51–65.

MENDELSOHN, OLIVER and MARIKA VICZIANI. 1998. The Untouchables: Subordination, poverty and the state in modern India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MISHRA, VINOD. 1999. The Dalit question. In, Selected Works, pp. 192–94. New Delhi: Central Office of the CPI (ML).

MUKHERJEE, ANATH BANDHU. 1980. The Chamars of Uttar Pradesh: A study in social geo- graphy. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications.

MURUGKAR, LATA. 1991. Dalit Panther movement in Maharashtra: A sociological appraisal.

Bombay: Popular Prakashan.

NARAYAN, BADRI. 2004. Inventing caste history: Dalit mobilisation and national past. In Dipankar Gupta, ed., Caste in question: Identity or hierarchy?, Contributions to Indian sociology occasional studies 12, pp. 193–220. New Delhi: Sage Publications. O’BRIEN,

DONAL CRUISE. 2003. Symbolic confrontations: Muslims imagining the state in Africa. London: Hurst.

PAI, SUDHA. 2002. Dalit assertion and the unfinished democratic revolution: The Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

RAWAT, RAM NARAYAN SINGH. 2003. Making claims for power: A new agenda in Dalit pol- itics of Uttar Pradesh, 1946–48. Modern Asian studies 37, 3.

TARTAKOV, GARY. 2000. The politics of popular art: Maharashtra. In Shivaji K. Panikkar, Twentieth century Indian sculpture: Last two decades, pp. 100–107. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

THORNER, DANIEL. n.d. The agrarian prospect in India. New Delhi: Delhi University Press. VIRAMMA, JEAN LUC RACINE and

JOSIANNE RACINE. 2000. Viramma: Life of a Dalit. New

Delhi: Social Science Press.

Zelliot, Eleanor. 1970. Learning the use of political means: The Mahars of Maharashtra. In Rajni Kothari, ed., Caste in Indian politics, pp. 29–69. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

— — — . 1988. Congress and the Untouchables, 1917–1950. In Richard Sisson and Stanley A. Wolpert, eds., Congress and Indian nationalism: The pre-Independence phase, pp. 182–98. Berkeley: University of California Press.

— — — . 2001. The meaning of Ambedkar. In Ghanshyam Shah, Dalit identity and politics. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Interviews

Aherwar, S.P. and Babulal Aherwar. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP,

May 2000. Ambavadekar, Rahulan. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, March 2001.

— — — . Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, October 2004. Ambedkar,

Rajesh. Interview by author. Rudauli, UP, March 2001.

— — — . Interview by author. Rudauli, UP, May 1999.

Bahadur, Raj, Interview by author. Lucknow, UP, March 2001.

Balley, L.R. Interview by author. Jalandhar, Punjab, July 2006.

Bauddh, Tejram. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, November 1999.

Bharti, Makrand Lal. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, January 2000.

Chodhry, Madan Mohan. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, April 2001. Gautam, Siddh Gopal. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, April 2000.

Gupta, Dauji. Interview by author. Lucknow, UP, March 2005.

Kumar, Vijay. Interview by author. Allahabad, UP, November 2004.

Prasad, R.D. and M.L. Prasad. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP,

February 2001. Sagar, Bhagwati Prasad. Interview by author. Kanpur, UP, April 2000.

Sankhvar, Ammaji. Interview by author. Rudauli, UP, May 1999.

Sankhvar, Disaram. Interview by author. Pukhrayan, UP, November 1999.

Sankhwar, ‘Tiwari’. Interview by author. Balahpara Karan, UP,

March 2001. Sharma, Jatan Ram. Interview by author. Patna, Bihar, March 2005.

Tyagi, S.P. Interview by author. Kanpur UP, March 2000.

Party Documents

Bharatiya Dalit Panthers, Uttar Pradesh. Undated. Hamari mang.

Bharti, Shiv Prasad. 1985. Ek sansmarang. In Congress smarika, l885–l985. Kanpur. Ram, Kanshi. 1982. The Chamcha Age: An era of the stooges. New Delhi.

Press Articles

Bhu Bharti, September 1981. Kanpur mein 25 hazar Harijanon ka dharm pariwartan kyon nahi hua?

India Today, 30 April 1994. A new assertiveness.

— — — . 28 July 1997. Statue symbols.

Pioneer, Allahabad. 22 April 1969. Ambedkarites clash with police: 30 hurt.

— — — , Lucknow. 15 April 1973. Ambedkar statue unveiled: mayor’s tributes.

— — — . 15 April 1997. Letters to the editor.

Samta Sainik Sandesh, New Delhi, 1, 5. 24 June 1981. Babasaheb’s portrait desecrated.

— — — , 1, 16. 1 December 1981. All accused in Kanpur Ambedkar Jayanti case acquitted.

Times of India, New Delhi. 28 September 1995. BSP may force early polls: Kanshi Ram.

Nicolas Jaoul is an anthropologist at the CNRS, a member of the IRIS and an associate member of the CEIAS. Based on long field work, his PhD dissertation, defended in 2004, addressed the emancipation movement of Uttar Pradesh’s untouchables (Dalits). He has since developed his ethnographic approach of the underprivileged in India by undertaking regional comparisons of the Dalit mobilization, looking into communist pesants in Bihar, or the relationship between the Dalits and Hindu nationalism or Gandhism.

[1] Different terms are used to refer to those segments of the population treated as ‘Untouchables’, according to Brahminical standards, because of their ‘unclean’ occupations such as leather-work, sweeping and scavenging, weaving, cremating the dead, and so on. The term ‘Scheduled Castes’ is an official category, framed by the colonial state in 1935 to implement special policies towards the Untouchables following the Poona Pact agree- ment between Gandhi and Ambedkar. The term ‘Harijan’ (‘People of God’) was invented by a Gujarati poet of the 17th century and popularised by Gandhi after 1932 in order to promote the acceptance of Untouchables by other Hindus as members of their religion. The term ‘Dalit’ (‘crushed’ or ‘oppressed’) is a less euphemistic term which has been in use since the 1910s. In fact it was used by the Arya Samaj and later by Jagjivan Ram. (Both are considered as representing the non-radical reformist approach to Untouchability, where upper castes took the lead in promoting reform, though of course both were seen as radical compared to conservative upper-caste Hindus.) The term ‘Dalit’ became associated with radicalism when it was re-popularised in the 1970s by radical Ambedkarites such as the Dalit Panthers and later by the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). Today the use of ‘Dalit’ has become widespread in many parts of India, including UP. In this article I use different terms, according to the historical context.

[2] Tartakov also informs us that Ambedkar statues had been installed in Maharashtra, at non-official functions, by Ambedkar’s own Mahar followers since the early 1950s — even before Ambedkar’s death.